Terminology – Definitions and explanations of palaeo-sea-level terminology References – download a spreadsheet of references NOTE: all elevations are quoted relative to LMSL unless otherwise stated.

Palaeo-sea-level at the last interglacial period (LIG) at Bermuda, the Bahamas, Florida, Australia and the Mediterrenean.

Introduction

Influential Pleistocene palaeo-sea-level studies were undertaken in Barbados (e.g. Mesolella et al., 1969) and New Guinea (e.g. Chappell, 1974) in the late 1960s and early 1970s. These sites of rapid tectonic uplift were considered ideal for such research, because the record of successive ancient sea level “highstands” were not overwritten. Rather, fossil coral reef tracts were preserved in upward-ageing flights of terraces. The primary objective – to establish eustatic palaeo-sea levels (GMSLs) at respective interglacial periods – was achieved through the measurement of the elevation of radiometrically-dated reefs and by then making corrections for uplift. In this process assumptions were made with respect to the rate of uplift, its constancy and the palaeo-water-depths at which the reef-forming corals grew. These assumptions have, however, not stood up well to the test of time (50).

Localities which were considered tectonically stable attracted increasing attention from researchers in the latter part of the 20th century. These included Bermuda, the Bahamas, Florida, Australia and the Mediterrenean. In addition to their putative tectonic passivity they were considered, at least initally, to be little affected by GIA. Despite uncertainties which have emerged, with respect to claims of vertical stability, these localities remain united by intimated LIG sea level (LRSL) ranges which are remarkably similar.

Bermuda

The identification and interpretation of LIG deposits on Bermuda

Sayles (1931) (22) concluded that the Sangamon stage – the last interglacial period (LIG) – is represented on Bermuda by the conglomeritic Devonshire marine limestone (now assigned to the Rocky Bay formation). This has been affirmed by U-series radiometric dating of Devonshire coral fragments, which beginning with those collected by Broecker and Kulp (1957) (84) have yielded U-Th radiometric ages as follows: 130 ka to 120 ka (84); 134 ka to 118 ka, (4); and 126 ka to 114 ka (11,19). The last of these age-ranges, derived from 11 coral fragments (Muhs et al, 2002 and 2020), is considered the most reliable and suggests that coral growth, on Bermuda was most active in the latter half of the LIG when LRSL peaked.

A close stratigraphical association between emergent ancient marine deposits and eolianites (carbonate dunes), on Bermuda, was recognised by early researchers (2) (3). Despite partial submergence of many of the aeolian slip-face strata, it was concluded that dune building was triggered when sea level was close to its peak during interglacial periods. Bretz 1960 (2), and others that followed (Land et al, 1967) (3), correlated Bermuda’s most prominent marine and dune deposits, then known as the Devonshire and Pembroke formations, with the marine highstand of the last interglacial period (LIG). This was considered a reversal of Sayles 1931 (12) hypothesis that dune building was the outcome of low, or falling, sea levels which exposed “great flats” of sand to the wind.

Anomalously high LIG “marine” deposits on Bermuda

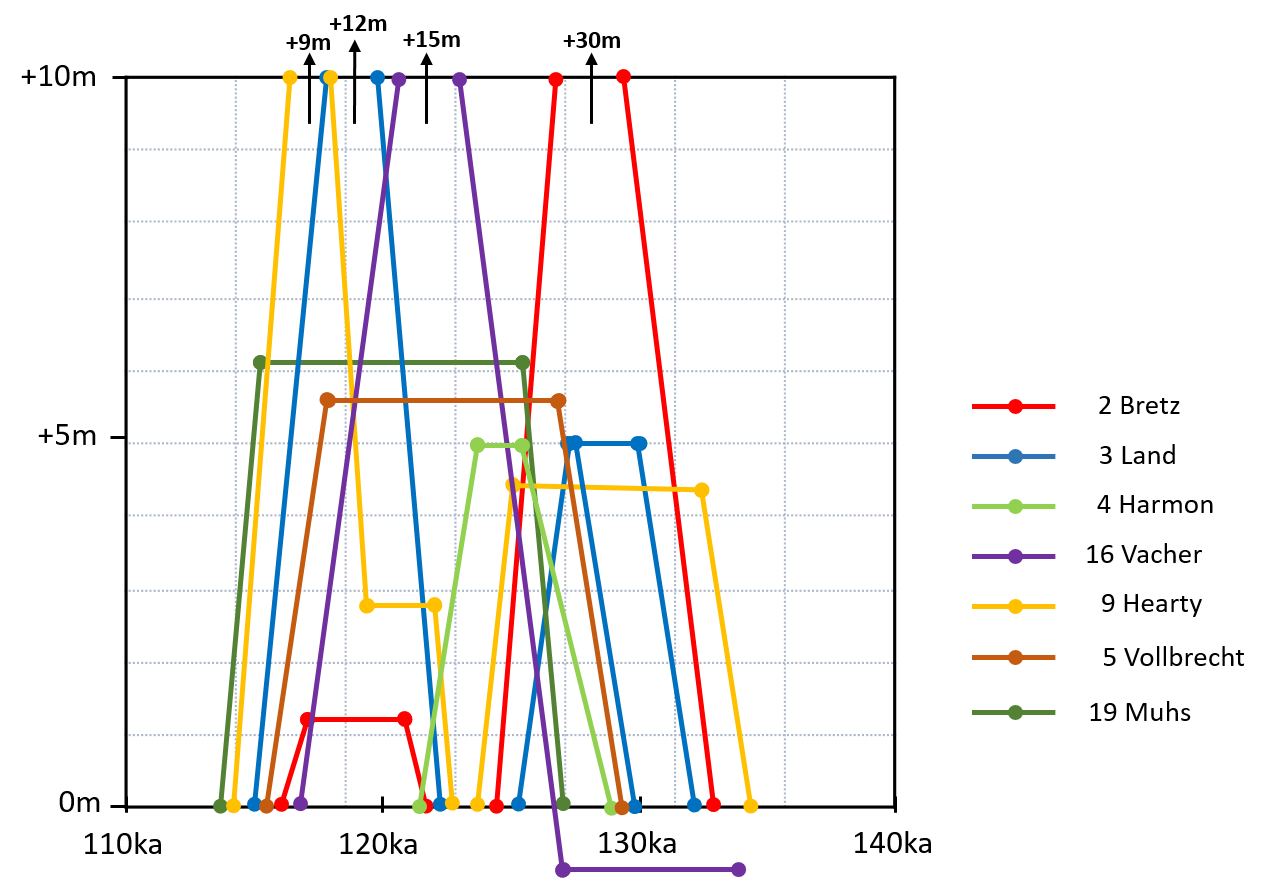

On Bermuda’s north shore, for example at Blackwatch Pass, calcarenites with low-angle, planar beach-like stratification were for many years speculatively correlated with the Devonshire marine deposits. The high elevation of the north shore strata, convinced Bretz (1960) (2) that local relative sea level (LRSL) at the LIG reached up to +30m. He asserted that this sea-level peak was followed by a regression below local mean sea level (LMSL), and that a minor re-advance to ~ +1 m preceded a final regression. (See Figure 13a, below).

Land et al (1967) (3) envisaged a rapid sea level rise to + 5 m, recorded by a conglomerate-filled notch at Hungry Bay, before a fall to slightly below present LMSL when substantial LIG dune ridges were formed. Then, based on the north shore strata (as per Bretz) and the discovery of a high conglomerate on the south shore – at Spencer’s Point – they postulated that sea level rose to +12m or more at the end of the LIG.

Subsequently, Vacher (1972) (16) proposed that a sea-level highstand just below present LMSL endured through the early part of the LIG, accounting for widespread formation of dunes which are now partially submerged. Then, by his account, sea level rose in the middle of the LIG to as high as +15m.

Much later, Hearty and Kindler (1998) (9) contended that LIG commenced with +4.5m sea-level transgression which persisted long enough to build large interior dune ridges. This was followed by a second oscillation in which sea level dipped below present LMSL and then rose to ~ + 2.5 m for a brief period before surging to at least +9m (9,44). ( see Figure 13 a)

Bermuda studies, such as those listed above, which cite evidence of sub-stage LIG oscillations involving two or more peaks and surges to much greater than +9 m (9,44) have not stood up to scrutiny. On the north shore, emergent low angle strata identified in the past as marine, more convincingly meet the criteria of aeolian strata (23). Indeed, they would have been identified as such had the parsimony principle been applied. In addition to questionable interpretations of their origins, these deposits lack material which can be reliably dated. For these reasons, LIG palaeo-sea-level curves based on research in Bermuda in the 1960’s, 1970’s and 1980’s are, in the main, controvertible.

An exception among these early Bermuda sea level curves was that produced by Harmon et al (1983) (4). This relied less on putative coastal sea level indicators and more on the relationship of speleothem growth chronology to sea level changes in caves. With this approach, it was concluded – consistent with more recent research (19) – that LIG LRSL at Bermuda peaked only once, at approximately +5m.

In search of a consensus value for peak LIG GMSL

The concept of a globally applicable reference level of +6m for the elevation of peak LIG global mean sea level (GMSL) originated with the observations of emergent coral reefs made by Veeh (1966) (88) throughout the Pacific and Indian Oceans.

Because of Bermuda’s position near the middle of an oceanic plate and the supposed absence of any evidence of deformation (now refuted), a default assumption of tectonic stability was initially adopted (4). For several decades Bermuda was portrayed as the “pre-eminent Quaternary type-site for (eustatic) sea-level” (31), a “tide gauge’” (3) and an oceanic “dipstick” (12).

A marine conglomerate infilling a +5m notch at Hungry Bay on Bermuda’s south shore was assumed to corroborate Bermuda’s stability (3) because of its near coincidence with the +6m global reference level.

More recently, global estimates of LIG GMSL have been expressed in terms of ranges which, if anything, have widened over time to, for example +2m to +9m (See Chapter 13). The greater range can be attributed to increasingly accepted uncertainty over effects of vertical land motion (VLM) associated glacio-isostatic adjustment (GIA) and tectonism.

Facies analyses of a succession of arenaceous shoreface and foreshore beach deposits, would yield more robust estimations of RSL than simple elevation measurements of isolated conglomerates, as has been the approach often adopted in Bermuda – for example at Hungry Bay and Spencer’s Point. Unfortunately, on Bermuda, LIG high sea level imprints do not include such facies assemblages which effectively constrain the position of LRSL within a narrow elevation range. A well defined boundary between sub-tidal and inter-tidal beach facies which is considered to provide a relatively precise measure of palaeo-sea level (31) is absent. Unlike marine deposits of the penultimate Interglacial (PIG) (25), those of the LIG are coarse and poorly sorted. Their stratification is indicative of a high energy erosional environment not conducive to the formation of stable foreshore and shoreface structures. Having analyzed these Devonshire marine deposits of the south shore Meischner et al (1995) (5) and Muhs et al (2020) (19) were able to estimate peak LIG RSLs of ~+6 m and +5 m to +7 m, respectively. A credible average RSL representing a “highstand” has not, however, been established to a greater precision than a range of +2 m to +7 m.

Despite this remaining uncertaintity, the upper constraint on LIG RSL, at Bermuda, of + 7 m, establsihed by Muhs et al (2020) (19), is an important development. Two terrestrial-limiting sea level indicators in the form of a palaeosol (19) and of a speleothem (4,24) which respectively would have been eroded or would have ceased to grow had LIG sea level exceeded +7 m, support the Muhs et al (19) conclusion. Furthermore, according to Harmon et al (1983) (4) there is no evidence for LIG seawater flooding in caves above an elevation of +5m.

Missing evidence of a prolonged LIG highstand at Bermuda

While LIG LRSL at Bermuda, may have peaked at close + 7 m, it is important to point out that evidence for a sustained highstand near this level at the LIG, indeed at any interglacial, is scant. Comparisons have been made between Bermuda’s LIG sea level record and that of stable areas such as the Bahamas (9) (31), Florida (52) and western Australia (31). Unkike Bermuda, however, these other localities feature emergent in-situ LIG coral reefs which provide reliable minimum LRSL elevations as well as robust radiometric ages. On Bermuda, there are no unequivocal growth-position fossil corals (24). The majority of evidence cited in support of an LIG peak RSL at + 5 m to + 7 m consists of clastic deposits (including coral fragments) and occasional erosional features – either of which could have formed in a space of a few hundred years. The Devonshire marine deposits of the LIG comprise “erosional deposits that formed along cliffs and pocket embayments” (10) They do not evoke a mature coastal environment representative of a prolonged highstand.

In addition to the coral reefs, other indicators of sustained highstands which are all but absent in Bermuda are emergent phreatic caves. These are caves which are created by dissolution of limestone in the saturated zone. They are extremely rare in Bermuda (45), and those that are potentially of LIG age are only known to occur below present sea level. This contrasts with the Bahamas, where emergent phreatic caves are well documented at elevations of +1 m to +7 m – an elevation range which is consistent with formation at a prolonged LIG highstand (45).

As for ancient biological notches, which are reliable indicators of past prolonged sea level highstands, there are no emergent versions (attributable to a higher-than-present RSL) which have been conclusively identified on Bermuda. Certainly there is nothing to compare with the well-defined notch in the Bahamas, at approximately + 6 m, which has been attributed to the LIG (31) (44).

Vertical land motion (VLM) affecting Bermuda.

Bermuda’s wide repute for vertical stability has been dismantled over the years. Its palaeo-sea-level record has been reassessed in the context of glacio-isostatic adjustment and tectonic instability, as evidenced by earthquakes and faulting (25). The range of peak LIG LRSLs of +5 to + 7 m at Bermuda – espoused by Muhs et al (2020) (19) – while consistent with the global consensus of peak (eustatic) LIG GMSL, they are significantly lower than the +11m to +13m levels predicted by GIA simulations for Bermuda (28, 80). GIA at Bermuda has, in effect, not been successfully modelled. This may be because the models are flawed or because LRSL is contaminated by tectonic vertical land motion VLM.

As a result of Earth’s dynamic topography, manifested as VLM, peak LIG sea level observed as local RSLs, is not expected to be the same across the Earth’s surface, nor will the timing of peak sea level be synchronous (26). Peak LRSL for Bermuda, as simulated by GIA models, start at +5 m and rise to +11 m to 13m by the end of the LIG. The models show that, even with no change in LIG GMSL, (eustatic sea level) a GIA-driven late peak is expected at Bermuda and the Bahamas. There is no need to invoke a rapid change in GMSL or ice volume to explain these field observations (26).

Not only is the GIA-corrected sea level elevation of +11 m to +13 m, unsupported by sea level indicators in the field, but also the modelled sea level curve which infers a sustained highstand lasting at least 10ka is un-corroborated. As alluded to, above, the emergent reefs and caves that would attest to a prolonged highstand are absent.

Conclusions on Bermuda

LRSL at Bermuda during the LIG peaked at +5m to +7m. There is, however, no evidence that there was a sustained highstand at this elevation or indeed at any elevation above present LMSL. Bermuda is considered to be influenced by GIA effects associated with ice-sheet loading and unloading in north-eastern USA. GIA modelling indicates that LRSL at Bermuda should have peaked at +11 to +13 m towards the end of the LIG. This is significantly above the maximum level of +5 to + 7 m observed on Bermuda. Either the models are flawed or Bermuda’s sea level record is contaminated by VLM associated with tectonic instability, of which there is good evidence.

The Bahamas

Contradictory relative sea level interpretations from LIG coral reefs.

The Bahamas Islands are thought to be one of sources from which an early consensus elevation of +6m LIG GMSL, or eustatic sea level, was established (31). They were considered to be tectonically stable and remote from the influence of northern hemisphere continental ice sheet activity. Coral ages of ~125 ka and at least one prominent notch ~ +6 m ASL at the Bahamas were consistent with age and elevation data which had previously been found on the coastlines of the Indo-Pacific (86).

Ages of ~130 ka to ~ 120 ka for in-situ coral heads which “grew upward to a mean low sea level ∼ +6 m” were reprted by Chen et al. (1991)(85). However, a LIG LRSL of +6m was challenged by Hearty et al. (2007) (31) on the basis that the majority of the MIS5e coral-reef tops do not exceed +2.5 m. Instead, it was proposed that LRSL stood at +2 to +4m for most of the LIG, from 132 to 125 ka. After a short-lived dip, it then rose rapidly to +6 to +9 m for a brief period during which the +6 m notch was formed (44).

Constraints on relative sea levels imposed by sea level indicators

The formation of phreatic caves, which occur in the Bahamas at +1 m +7 m, have been correlated with the LIG through stratigraphical analysis and radiometric dating. Since such caves could only have formed in saturated limestones below sea level, their elevation constrains RSL to a minimum of +7m. It is argued, because cave formation by dissolution is a slow process, that this contradicts the assertions (31) (44) that LIG was stable at around +2.5m for a long period and only surged very briefly to +6 m, or higher, towards the end of the LIG.

More recently a review of sea level indicators (SLIs) in the Bahamas has buttressed the case for a sustained LIG LRSL at ~+5.5 m. These indicators included marine sedimentary structures as well as LIG patch reefs, with tops at + 2 to +3 m, which were estimated to have grown in palaeo-water depths of 3 m (85, 88). In situ corals younger than 125 ka have been found at even higher elevations from which a potential rise in sea level to more than +6m at the Bahamas is inferred (Dutton et al., 2022)(88).

Specifically, on New Providence Island the LIG deposits evidence three phases of LRSL: an early transgression that peaks at ~ +5.6 m, followed by an ephemeral fall in sea level below +1.7 m, and then a rise in sea level to +6.0 m that down-steps before dropping rapidly at the end of the LIG. The first sea-level highstand is thought to have occurred at 128–125 ka and the second at between 118–125 ka (88).

Evidence in favour of tectonic stability

While LIG foreshore deposits do exist at over +8 m (47) the slower-responding coral reefs only rise to a maximum of +2 m to +4 m, which is inconsistent with tectonic uplift. On the other hand, tectonic subsidence affecting the Bahamas platform has not been ruled out. Some authors have applied subsidence rates on the order of 1 to 2 m per 100 000 years (88). The notion of net subsidence is, however, seemingly contradicted by ancient phreatic caves and foreshore sedimentary deposits at elevations in excess of + 7 m.

GIA at the Bahamas.

Laterally extensive paleosea-level data from across the Bahamian archipelago has been used to evaluate a range of earth deformation models to provide more accurate estimates of GMSL (Dyer et al., 2021) (92). The highest elevation of the contact between aeolian facies and underlying beach facies was adopted as a sea level indicator (SLI) to establish LRSLs across the span of the islands.

The study (92) predicted that the highest LRSLs would be recorded towards the end of the LIG and on the northern most of the Bahamian islands, being closer to the North American LIG ice sheet and therefore most affected by GIA subsidence. On the ground, observed maximum elevations of beach facies SLIs were reported to decline in elevation from +6.7 m at the north of the archipelago to + 2.3 m in the south (92).

By removing the GIA component from the Bahamas data, Dyer et al. (2021)(92) derived a residual GMSL (eustatic) LIG curve. It was concluded with a high degree of probability that peak GMSL during the LIG period was between +1.2 m and + 5.3 m relative to present GMSL, which as a range is significantly lower than many previous estimates.

Conclusions on the Bahamas

In the Bahamas, there is some uncertaintity associated with the use of coral reefs as sea level indicators (SLIs). The water-depth range in which key coral species are capable of thriving is substantial. Nonetheless a reliable constraint on minimum relative LIG sea level (LRSL) of ~ +2.5 m has been established based on the elevation of the emergent reef-tops. Also, most agree that an estimated peak LRSL of ~+7 m is justified. It is the duration of “highstands” at intervening elevations that has been contentious.

GIA, it is argued, caused increasing isostaic subsidence at then end of the LIG and towards the north of the Bahamas archipelago SLIs are at their highest. After the LRSLs, derived from the relative sea level imprints, were corrected for this subsidence, a range for LIG global mean sea level of + 1.2 m to + 5.3 m was yielded.

Florida

Relative sea level estimates from fossil coral reefs

As with the Bahamas emergent ancient LIG coral reefs in Florida are estimated to have grown in palaeo-water depths of approximately 3 m. This compares well with the position of sea level interpreted from the elevation of contemporaneous oolitic shoals in the region (88).

Based on elevations of sedimentary and coral sea-level indicators (SLIs) in the Lower Keys, LIG local relative sea level (LRSL) is estimated at +1 m to +5.7m . In the Upper Keys, LIG reefs are found at +3.4 to +5.3 m from which LRSLs of +3.6 m +8.3 m are inferred (52). While further north in the Miami region LIG LRSL is believed to have peaked at +8.3 m to +8.6 m. In terms of timing, many of the coral U-Th measurements appear to record ages consistent with growth during the latter portion of LIG (e.g., after ∼123 ka) (88).

Vertical stability of Florida

Florida is considered to be tectonically stable (52) (56), but subject to GIA. Unlike Bermuda, but like the Bahamas, there is reasonable agreement between field interpretations of LRSLs and those generated by GIA models (19).

The elevation of LIG GMSL (eustatic sea level) estimated at +6 m to +9 m by Dutton and Lambeck (2012) (26) is corroborated by Muhs et al. (2011) (52), who posit that palaeo-sea level in Florida (situated in an “intermediate field” region with respect to GIA effects) stood at +6 m to +8 m during the LIG.

Although there is some evidence for multiple peaks in sea level in the Florida LIG depositional record, other studies find no convincing evidence in terms of geomorphic, stratigraphic, or geochronologic observations (88).

Conclusions on Florida

LIG fossil corals reefs are preserved at up to approximately + 5 m in the Florida Keys and along the east coast of the Florida peninsula. Based on these elevations and a 3m palaeo-water depth, estimates of peak LRSL range up to nearly +9 m. According to Muhs et al. (2011) (52), this corresponds well with the widely accepted range for LIG GMSL. If this is correct then Florida has not been subjected to signifcant tectonic or GIA-related vertical land motion since the LIG.

Australia

Variations in relative sea level estimates

In the early days of Pleistocene sea-level research, Australia was considered to be a stable datum where reliable eustatic elevations could be determined directly from preserved sea level imprints. Local relative sea level (LRSLs) interpreted from coral reef sea-level indicators (SLIs) of LIG age were, however, generally lower than the widely adopted value for LIG GMSL of approximately + 6m (40).

The tops of coral reefs in the age range of 127 ka to 119 ka stand at +2 m in southern Australia (46)(83) and at +3 m in western Australia (34)(40). In contrast to these very extensive low lying LIG reefs, corals dated to the late LIG at up to +9.5m (87) and palaeo-shoreline features from zero to +10.4m (63) have been reported in west- central Australia (63). This inconsistency of LRSL elevations across Australia, contradict claims of continent-wide tectonic stability (83)

Vertical land motion considerations

With the refinement of glacio-isostatic adjustment (GIA) models it became evident that even far-field locations such as Australia were not beyond the reach of related vertical land motion (VLM). Model simulations have indicated that the GIA at Australia has amounted to approximately 2m of subsidence since the LIG (87). Based on LRSLs interpreted from the southern and western Australian LIG reefs it is inferred that GMSL stood at +5.5m (30) for a lengthy period during the LIG, which is neatly in accordance with the consensus global value of ~+6m.

The anomalous high relative sea level indicators at +9.5m (87) and +10.4m, mentioned earlier, which are not consistent wth GIA modelling have been attributed to a late surge in MIS5e sea levels (34)(87) which putatively corroborates evidence of similar events at other locations outside of Australia (31). An alternative explanation, alluded to earlier, is tectonic instability as evidenced in western Australia by folding, faults and earthquakes (63, 66).

Conclusions on Australia

There are vast expanses of emergent LIG (127 ka to 119 ka) coral reefs on Australia’s south and west coasts at maximum elevations of approximately +2 m to + 3 m, respectively. These are interpreted as products of a LRSL which stood just above the reef top at close to + 3 m. After correcting for a contribution of GIA related subsidence, the data from Australia are indicative of a prolonged early to mid LIG GMSL at approxmately + 6 m relative to present GMSL.

The Mediterrenean

Western Mediterranean is considered a generally stable tectonic setting (59). LIG phreatic overgrowths on speleothems in Mallorca record LIG RSLs of +1.5m to +3m. (48)(77). Mediterranean coastal deposits and coral terraces are preserved at +2m to +7m (53). Well defined tidal notches along the Sardinian coast are found in a similar range of +3.5m to +5.5m (59). This is supported by LIG phreatic speleothem overgrowth in a Sardinian cave at +4.3m (58).

In Northern Israel a shoreline sequence accurately records RSL which stood at +1 to + 3.5m for most of the LIG but following some minor oscillations rose to approximately +7m (61). It was concluded from GIA modelling that GMSL stood between 0.8 m and +8.7 m for most of the LIG period.

Conclusions on the Mediterrenean

The Mediterrenean is considered to be a relatively stable region with reliable sea level indicators in the form of notches, speleothems and sedimentray deposists. The range of LIG LRSL positions are consistent with those at the other locilities, discussed here, and attest to a GMSL in a range of approximately + 2 m to +7m relative to present GMSL.

Overall conclusions and the implications for Bermuda

LIG local relative sea levels (LRSLs) estimates at Bermuda, the Bahamas, Florida, Australia and the Mediterrenean for the most part fall in a range of + 2 m to +9 m albeit skewed towards the lower end. In the past this correspondence was considered consistent with putative tectonic stability at all of the localities, However, subsequent recognition of their susceptability to differing degrees of GIA has effected a re-evaluation. Bermuda’s LIG LRSL range of + 5 m to + 7 m, is not consistent with values simulated by GIA models which take into account its relatively northern location.

LIG sea level indicators (SLIs), such as coral reefs support sustained RSLs in the range of + 2 m to + 7 m. There is, however, well documented evidence of RSLs at + 8 m, or more, at each of the localities. These are variously attributed to surges in sea level or to two peaks, one of which was sustained at a lower elevation than the other.

On Bermuda, reports of high LIG SLIs at > +10 m have been largely been rebutted. In actuality, the evidence for a sustained LIG LRSL above pesent sea level (LMSL) is dubious. Unlike the other three localities, there are no in situ emergent LIG coral reefs on Bermuda. The evidence for an LIG LRSL which peaked at + 5 m to + 7 m is almost exclusivley derived from coarse clastic shoreface and foreshore depostis, which could easily have accumulated in less than one thousand years.

The objective of many Pleistocene interglacial palaeo-sea-level studies has been to establish peak eustatic sea level in order determine the volume of melt water added to the oceans. With this information, the extent of deglaciation and global temperatures could be estimated. With increasing acceptance that LRSLs everywhere include contributions from vertical land motion (VLM) related to tectonic activity and glacio-isostatic adjustment (GIA) this objective has been tempered. Bermuda, the Bahamas, Florida, Australia and the Mediterrenean have in the past all been cited as tectonically stable study areas not especially susceptible to GIA. This is no longer the case. The history of VLM at a given location is almost unknowable and for this reason GIA models are difficult to calibrate and to this point have not delivered convincing results.

It can be concluded that at the four the study areas in question, that LIG RSL was sustained at + 2 to + 9 m, perhaps with the exception of Bermuda. While undoubtedly they were subject to tectonically-related and GIA-related vertical land motion (VLM), it is arguable that these effects were relatively subdued. Accordingly, a sustained LIG GMSL elevation of + 5 m +/- 3 m (relative to present GMSL) can be surmised. There is some evidence that LIG GMSL may have peaked higher than this during a brief surge at a secondary oscillation.

At Bermuda, the absence of emergent in-situ coral reefs of LIG age, or for that matter of any age, is an observation that is largely ommitted from the literature – likely because it belies the narative of an LIG highstand above LMSL. There is, after all, a broad consensus globally that LIG GMSL (eustatic sea level) stood at least 2 m higher than present GMSL for thousnads of years. The absence of emergent LIG reefs on Bermuda is further confounded by existence, of modern reefs today, along the Bermuda’s shorelines and across the platform, which extend up to present sea level. From this it can be inferred that any peak LIG LRSLs, at Bermuda, were lower or of shorter duration than that of the Holocene. If the overwhelming evidence for sustained LIG global mean sea level higher than that today is accepted, then episodic land susbsidence at Bermuda must be invoked to explain an absence of an emergent reef record there.