This chapter provides an overview of the mid to late Pleistocene relative sea level record at Bermuda.

For a more exhaustive discussion of this topic as it applies to Bermuda and beyond please visit: Pleistocene palaeo-sea-level research.

Evidence of past positions of sea level

Evidence of low sea levels

Being close to the acme of a Pleistocene interglacial period, we are today experiencing high sea levels which have been exceeded on only a few occasions during the past 1 million years or so. Now is, therefore, not the most opportune time to examine field evidence of past sea level positions. Other than in regions of the globe where the land has been uplifted, the majority of surviving evidence is submerged and buried by modern marine sediments.

The best indications that sea levels at Bermuda have been lower than at present are provided by geological features which formed above sea level but are now submerged, such as fossil soils and cave formations including stalagmites and stalactites. Direct evidence of the very lowest sea levels, during glacial periods, are rarely observed. Limited investigations using small research submarines have, however, revealed wave-cut features on the flanks of the Bermuda seamount, from which the existence of ancient shorelines at considerable depths – at 60m and 115m below present sea level – are inferred (IL1).

Evidence of high sea levels

On Bermuda, there is a good record of the few occasions, during the last 1 million years or so, when relative sea level (RSL) was higher than at present. The evidence takes the form of ancient marine features, created by the sea, which are found above the elevation of their modern counterparts. Ancient limestone beaches (Figures 4g and 4h, Chapter 4) are examples which can provide a relatively precise record of sea level position at the time of their formation. On Bermuda, such beaches have been preserved at 3 to 4 m (up to 12 ft) above their present-day equivalents.

Erosional features (Figure 8a) and accumulations of rock debris, such as conglomerates and breccias), produced by wave action, can also be useful markers, of past high sea levels. More information on ancient marine deposits and their role in establishing past high sea level positions on Bermuda is provided in Chapter 4.

Biological evidence

Robust biological evidence of past high sea level events is puzzlingly rare on Bermuda, given the existence of other forms of elevated sea-level imprints, described above. In many other parts of the world, “raised” or “emergent” fossil coral reefs are the “go to” indicators of past high (relative) sea levels. Isolated examples that have been reported, on Bermuda, were poorly documented and cannot be verified. Indeed, during the process of mapping the geology of Bermuda (VA6) which spanned 5 years, the three authors found nothing that would qualify as an emergent, in-situ, ancient coral reef.

Albeit scarce, biological sea-level imprints do exist. Examples are found at Watch Hill Park in Smith’s Parish and on the shore of the Great Sound near Fort Scaur in Sandys Parish. At these localities, fossil molluscs which in life clung to, or bored into, inter-tidal or sub-tidal rock surfaces are today preserved intact, and articulated, “high and dry” above present sea level (Figure 8b). These small isolated colonies of fossil molluscs preserved above present sea level do not necessarily contradict the absence of in-situ coral reefs at the same elevation. It takes considerably less time for a submerged rock face to be colonised by molluscs than it does for a coral reef to form.

It is inferred, from the inability of coral reef growth to catch up with rising relative sea levels during interglacial periods at Bermuda, that prolonged highstands, recorded elsewhere in the world, did not occur here. The predominantly clastic nature – represented by beaches and conglomerates – of the emergent sea level imprints is consistent with short-lived RSLs (relative sea level) peaks which only briefly exceeded present day RSL.

Evidence from caves

Some of the most reliable indicators of past sea level positions – lower and higher than today – are found in Bermuda’s caves. Cave formations, or speleothems, such as stalagmites (Figure 8c) and stalactites form in air-filled chambers by precipitation of calcite from dripping or trickling water. A submerged speleothem is, therefore, proof of a past lower sea level.

Interruptions in speleothem growth can be related to climatic events but flooding of the cave by ground water in response to high sea levels is another likely cause. Careful analysis of the precipitated calcite layers within speleothems and age determination by U-series radiometric dating can reveal the time-span of interruptions in their growth. Geological investigations on Bermuda (HA1,WA1) have identified speleothem growth-interruptions, which have been attributed to submersion and, thus, have added significantly to our understanding of the sea level history.

Geochemical evidence

Small limestone islands such as Bermuda are saturated with ground water (fresh or saline) up to sea level. Above sea level the limestone is unsaturated. These two conditions – when the pores of the limestone are filled with water and when they are drained – are respectively termed phreatic and vadose. The dividing line, or plane, between them is known as the water table which lies close to sea level (within 0.5 m). Near the coast, sea water saturates the limestone below the water table and is responsible for marine phreatic cementation, which deposits high-Mg (Magnesium) calcite cement in the rock pores. This produces a vertically constrained geochemical signature unique to coastal limestones which have been submerged below the water table. This signature has been used as a marker of past sea level positions on Bermuda, most notably the high sea level at 200,000 years ago responsible for deposition of the Belmont Formation marine deposits (LA2,ME2).

The history of sea level fluctuations

Global climate has fluctuated dramatically since the beginning of the Pleistocene Epoch 2. 6 million years ago . For the past 1 million years or so the glacial-interglacial cycles have spanned roughly 100,000 years. Meaning, this was the interval between successive phases of maximum ice sheet formation – known as “glacial” periods – across the continents of the Northern hemisphere.

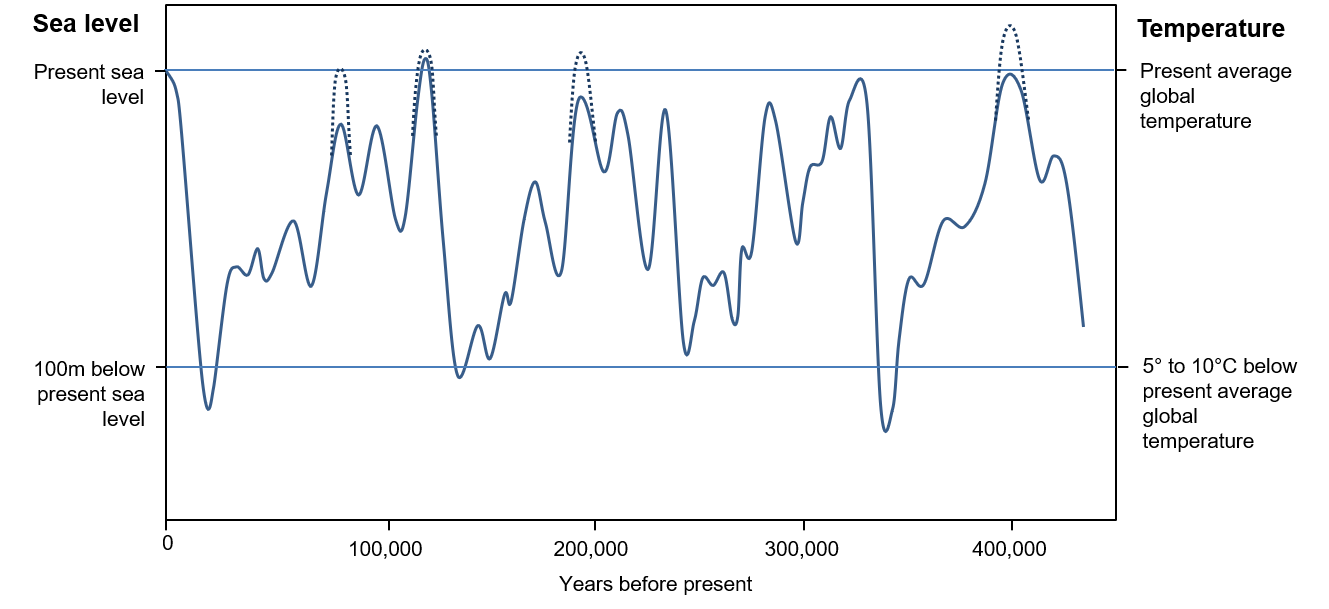

During glacial periods, large volumes of water were bound up in the ice sheets which covered up to one third of the earth’s land area. This water was released as meltwater during warm “inter-glacial” periods. In response, global sea levels rose and fell over a range of up to 120 m (390 ft) (Figure 8d). Rates of sea-level change sometimes exceeded 100 mm (4 inches) per decade.

At each glacial period Bermuda would have emerged as a single large island, we can call “Greater Bermuda” (Figure 1f, Chapter 1). The North Lagoon which is presently submerged to depths of 15 m to 20 m (60 ft) would have been transformed into a forested plateau. Neighbouring Argus, Challenger and Bowditch “banks” would have temporarily emerged from the sea.

Fossil soil layers and peat deposits buried within the sediments of the present Platform, or North Lagoon, (VO2,GI3) attest to the occasions (at each “Ice Age”) when the land area of Bermuda expanded to more than ten times its present size, as the lagoon waters drained away. Submerged remains of cedar trees found in St George’s Town Cut, Mills Creek and at Gurnet Rock represent more direct evidence of episodic lower sea levels that saw the transformation of the present sea bed into a forested landscape of Greater Bermuda.

When sea levels were high, during warm interglacial periods, the land area of Bermuda would have been close to its present size. Elevated ancient beach deposits and erosional features, mentioned earlier, indicate that on several occasions in the past Bermuda’s shoreline closely corresponded to that of today. And for relatively brief periods of time, sea levels at Bermuda exceeded its present level (Figure 8d). Where suitable unaltered coral fragments have been found in elevated marine conglomerates, their ages, as determined by radiometric dating, have been the basis for research into chronology of high sea level events at Bermuda, as described in Chapter 12.

Eustacy versus Isostacy

Rising and falling sea-levels during the Pleistocene Epoch were associated respectively with the onset of warm interglacial periods and cold glacial periods. Sea level change resulted, on the one hand, from the release of water to the oceans from melting continental ice sheets and, on the other hand, from the transfer of ocean water (as snow) to the land when ice sheets were re-forming. Respective increases and decreases in the volume of water in the world’s oceans caused “eustatic” sea level changes simultaneously across the globe.

Vertical movement of a land mass, or “vertical land motion”, causes changes in “relative” sea level. This is the level of the sea as measured against a datum on the land. During the Pleistocene, the cause of such changes at Bermuda were attributable, at least in part, to the loading and unloading of the North American continent by massive ice sheets which grew up to 3 km (2 miles) thick. Such changes in relative sea level in response to land movement are termed “isostatic”. The effect on Bermuda is explained in more detail below.

During glacial periods the great weight of glacial ice accumulating on the continental crust in the northern hemisphere caused it to downwarp and, relative sea level rose. Conversely, during inter-glacial periods, the continental crust rose, or rebounded, as it was relieved of the weight of ice, and relative sea level fell. Differences in the scale and timing of relative sea level movement are observed between northerly regions, where land movement, or isostacy, has been a significant factor, and those further south where sea level movement, or eustacy, has been dominant.

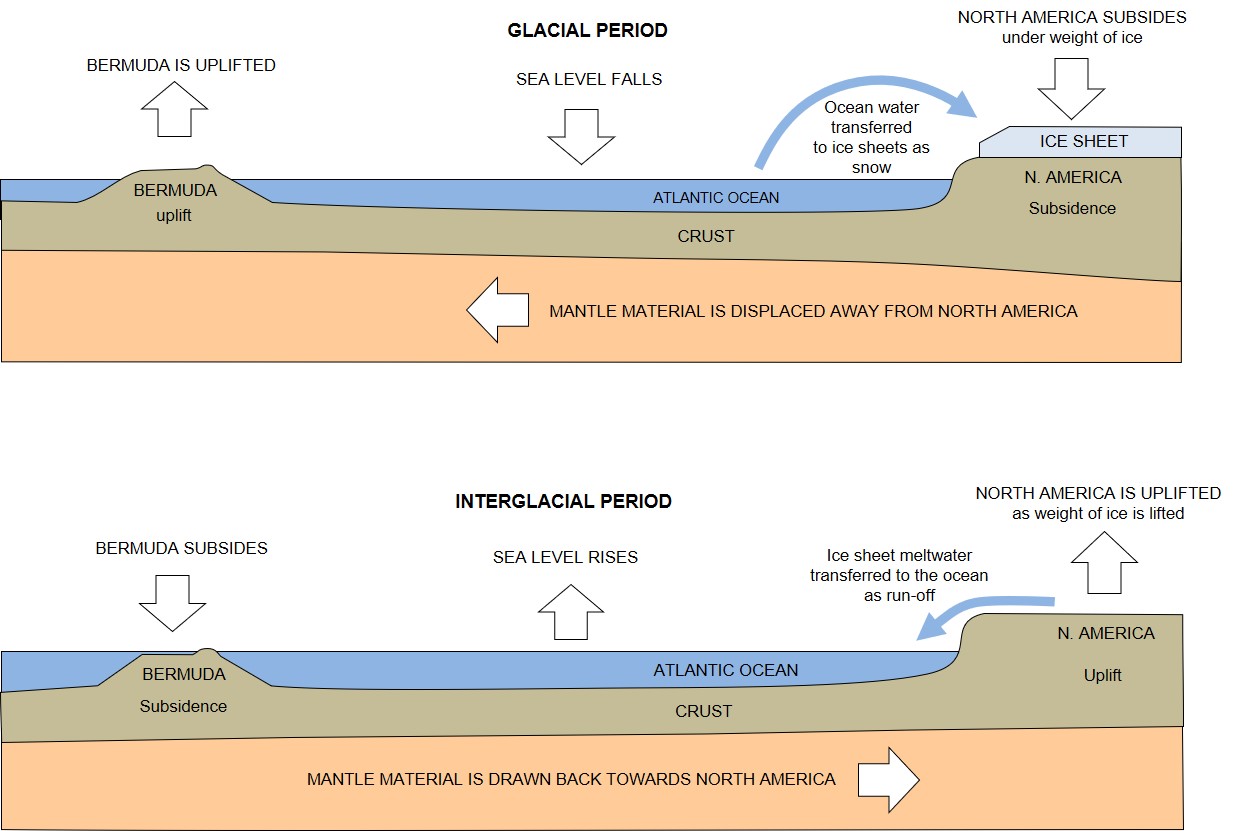

There are other less direct isostatic influences on relative sea level imposed by the Pleistocene climatic cycles. Bermuda, for example, while not having been subjected directly to ice loading, is close enough to North America to have been affected by the weight of large ice-sheets which episodically accumulated there. During glacial periods, viscoelastic mantle material was squeezed towards Bermuda from beneath North American crust, creating a “forebulge”, and Bermuda was uplifted. During interglacial periods the process was reversed, the forebulge dissipated, and Bermuda subsided (Figure 8e). These effects have been modelled but there is no consensus on their scale. It is generally agreed, however, that the cycle of uplift and subsidence of the Bermuda seamount would have caused exaggeration of relative sea level fluctuations. Indeed, evidence of higher peaks in relative sea level have been reported at Bermuda, during the Pleistocene epoch, compared to other locations around the world (Figure 8d).

Although the glacio-isostatic effect at Bermuda was an order of magnitude less than the eustatic effect on sea level, and was largely unrecognised or dismissed in 20th Century research, it is now known to have been significant. Glacio-isostatic adjustment (“GIA”) is considered to have contributed to a relative sea level history at Bermuda which is unique (DU1, WA1). Further discussion of this subject can be found here.